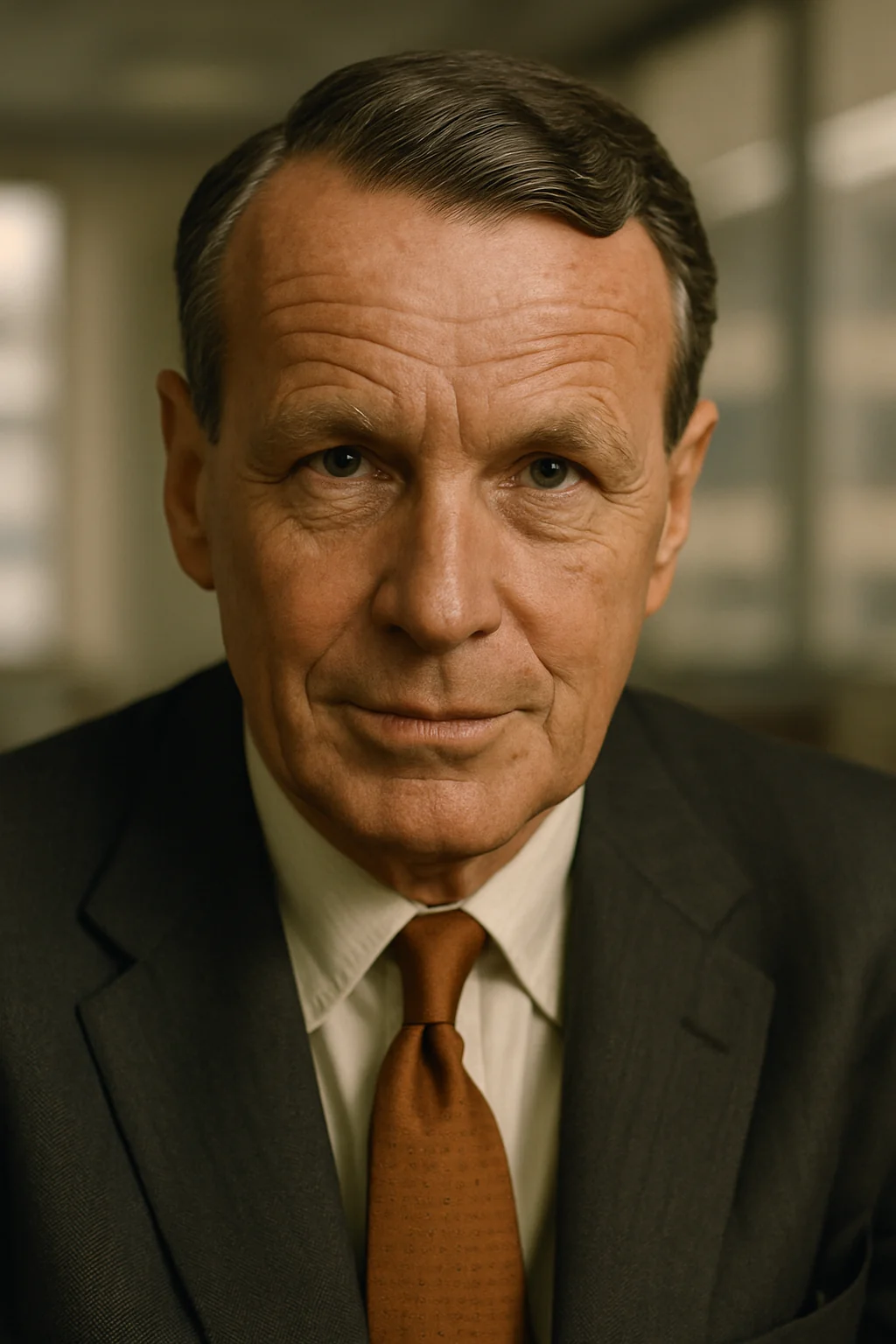

David Ogilvy

Quotes & Wisdom

David Ogilvy: The King of Madison Avenue Who Revolutionized Modern Advertising

David Ogilvy emerged as the defining voice of advertising during its golden age, transforming a fledgling industry into a respected profession through his unwavering commitment to research, persuasion psychology, and brand-building principles. A former farmer, door-to-door salesman, and British intelligence officer, Ogilvy brought an outsider's perspective when he founded his agency, Ogilvy & Mather, in 1948 at the unusually late age of 38. This diverse background shaped his unconventional approach, combining sophisticated cultural sensibilities with razor-sharp business instincts. His iconic campaigns for Hathaway shirts, Rolls-Royce, and Schweppes didn't just sell products—they created lasting brand identities that changed how companies communicated with consumers.

What truly distinguishes Ogilvy was his insistence that advertising must sell while respecting consumer intelligence, a revolutionary concept that challenged the industry's prevailing gimmickry. Both a meticulous craftsman obsessed with measurable results and a charismatic industry philosopher, his influence extends far beyond Madison Avenue into modern marketing, content creation, and persuasive communication. In exploring Ogilvy's remarkable journey, we'll discover how a self-taught outsider with uncompromising standards forever altered how brands speak to the world.

Context & Background

When David Ogilvy established his New York advertising agency in 1948, America was entering an unprecedented economic boom. World War II had ended, transforming the United States into a global superpower with a rapidly expanding middle class eager to embrace newfound prosperity through consumption. Television was beginning its dramatic rise, creating revolutionary opportunities for advertisers to reach mass audiences with dynamic visual messages. This post-war period marked advertising's coming of age—evolving from simple product announcements to sophisticated brand messaging as companies competed fiercely for consumer attention in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

Ogilvy's formative years provided him a unique lens through which to view this changing landscape. Born into a financially struggling but culturally sophisticated Scottish family in 1911, he absorbed classical education values of clarity, precision, and the power of language. His early career hopscotched remarkably—from prestigious British boarding school dropout to Paris chef apprentice, door-to-door stove salesman in Scotland, and social researcher studying consumer behavior. Perhaps most crucially, his stint as a British intelligence officer during World War II honed his understanding of persuasion and information gathering.

This diverse background placed him outside advertising's established pathways but equipped him with invaluable perspective as the industry was being redefined. The dominant advertising approach of the 1940s often relied on bombastic claims and repetitive slogans—techniques Ogilvy found intellectually insulting. Meanwhile, a parallel revolution in psychology and market research was emerging, with figures like Ernest Dichter pioneering motivational research that explored unconscious consumer desires.

Ogilvy entered advertising during this pivotal moment of conflicting approaches—old-school hard selling versus emerging psychological sophistication. He encountered a discipline hungry for professional credibility but often relying on intuition rather than data. Madison Avenue was transforming into a powerhouse of American business and culture, but still seeking its defining voice and ethical boundaries. These tensions—between art and science, between selling and brand-building, between short-term results and long-term reputation—created fertile ground for Ogilvy's revolutionary synthesis of research-driven, brand-focused advertising that respected consumer intelligence.

David Ogilvy cultivated an almost religious devotion to research that transformed how advertising effectiveness was understood. "I prefer the discipline of knowledge to the anarchy of ignorance," he famously declared, establishing a philosophy that differentiated him sharply from his contemporaries. While other agencies relied primarily on creative hunches, Ogilvy embraced data with fervor, establishing research departments within his agency decades before such practices became industry standard. This wasn't mere academic interest—Ogilvy had witnessed firsthand the power of consumer behavior insights during his early career at Gallup's Audience Research Institute, where he learned to trust statistics over assumptions.

This data-driven approach manifested in unorthodox ways that shocked Madison Avenue. Before creating campaigns, Ogilvy would immerse himself in product research—using Dove soap exclusively for months before crafting its famous "one-quarter moisturizing cream" campaign, or reportedly reading over 50 books about watch manufacturing before pitching Piaget. For the landmark Rolls-Royce advertisement, he spent three weeks studying technical materials before identifying the memorable fact that "at 60 miles an hour, the loudest noise in this new Rolls-Royce comes from the electric clock." This obsessive thoroughness earned him both respect and ridicule from colleagues who viewed such preparation as excessive.

Perhaps most revolutionary was Ogilvy's insistence on measuring results—something previously considered almost impossible for creative work. He tracked coupon returns, maintained meticulous records of campaign performance, and modified his approaches based on real-world results rather than creative intuition. This feedback loop influenced creative decisions in ways that initially seemed counterintuitive, leading him to prefer long-form copy that many contemporaries dismissed as outdated. "The more you tell, the more you sell," Ogilvy insisted, having verified through testing that information-rich advertisements often outperformed flashier alternatives. This marriage of creativity with data-driven decision-making created a template for modern advertising effectiveness that continues to influence digital marketing analytics today.

Though widely celebrated as advertising's most influential figure, David Ogilvy maintained a complex, often contradictory relationship with the industry that made him famous. He frequently lambasted the profession's ethical shortcomings while simultaneously working to elevate its standards. "I do not regard advertising as entertainment or an art form, but as a medium of information," he wrote, directly challenging the creative revolution championed by rivals like Bill Bernbach during the 1960s. This tension between Ogilvy's commercial pragmatism and his aspirations for advertising's cultural impact defined much of his career and created a fascinating contradiction: the industry's greatest champion often seemed its harshest critic.

Ogilvy's perspective was shaped by genuine contempt for manipulative advertising practices. He rejected bait-and-switch tactics, misleading claims, and creative work that prioritized awards over sales results. "The consumer isn't a moron; she's your wife," became his most famous maxim, capturing his belief that respecting audience intelligence was both morally right and commercially effective. This ethical stance often put him at odds with clients and industry peers who sought shortcuts to consumer attention. In meetings, he was known to abruptly terminate relationships with potential clients whose products he considered inferior or whose values contradicted his own—a remarkable stance in an industry notorious for accommodating any paying customer.

This moral compass extended beyond client relationships into his management philosophy. Ogilvy created agency environments that valued research and results over office politics—famously maintaining notecards detailing employee strengths rather than relying on personal favoritism. He implemented what he called "divine discontent," a management approach that balanced praise with relentless quality standards. His internal memos became legendary for both their inspiration and brutal frankness, sometimes publicly criticizing work that failed to meet his standards. These high expectations created both devotion and fear among employees, with Ogilvy alternately described as a nurturing mentor and demanding tyrant. The contradiction reflected his fundamental view of advertising: a profession that could and should aspire to something greater than it had yet achieved.

Behind Ogilvy's carefully cultivated image as advertising's distinguished statesman lay fascinating contradictions and quirks that revealed a more complex character. Despite his aristocratic presentation—complete with tailored suits, pipes, and formal mannerisms—Ogilvy harbored deep financial insecurities stemming from his family's financial struggles. This paradox manifested in peculiar spending habits; the same man who owned a French château insisted on using both sides of paper for memos and personally switched off lights in empty conference rooms to save electricity. When traveling for business, this millionaire agency head often stayed in budget hotels, explaining to confused colleagues that he preferred saving money to luxury.

Ogilvy's creative process involved surprising rituals. Before tackling difficult writing projects, he would drink half a bottle of rum and play Beethoven's symphonies at high volume, creating conditions for what he called "controlled irrationality." He crafted most of his famous advertisements not in a sleek Madison Avenue office but in a rustic hunting cabin in rural Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where he would retreat for days of intense concentration. This solitary creative process contrasted sharply with the collaborative brainstorming approaches favored by most agencies.

His personal resilience was remarkable but rarely discussed. Before his advertising success, Ogilvy endured multiple career failures and a nervous breakdown that required hospitalization. These experiences shaped his empathetic management style with struggling employees. Later in life, while running his agency's international operations, he suffered from significant health issues, including chronic depression. Yet he maintained exhausting work schedules well into his seventies, often conducting business from hospital beds during frequent illnesses. This meticulousness in maintaining appearances perhaps explains the pristine public image he cultivated—one that masked the insecurities and health struggles behind his achievements until long after his retirement to France, where he finally allowed himself to loosen the carefully constructed persona that had defined his professional life.